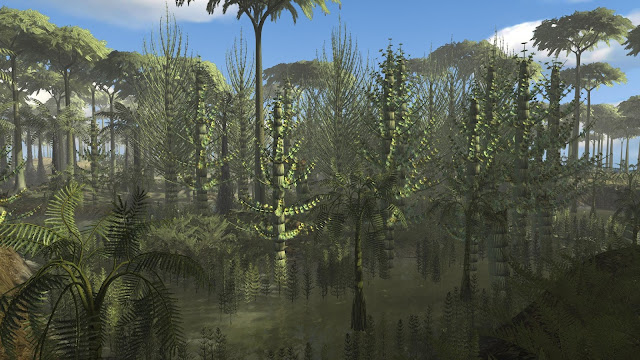

A change in prehistoric climate, brings a transformation of the landscape. The arrival of gymnosperms & dinosaurs.

Throughout the Permian period, which marked the conclusion

of the Paleozoic era and the commencement of the Mesozoic era, the earth’s

climate changed from warm, moist and humid, to cooler and much drier (Rost

1998). During this period, known as the dinosaur era, the dominance of seedless vascular plants throughout

the prehistoric landscape came to an end.

|

| Artist impression of Gymnosperms and dinosaurs during the Mesozoic era |

Seeded vascular plants are true

terrestrial plants (Willis & Mcelwain 2014). With unique life cycles, which

allow them to thrive in much drier climatic conditions, seeded vascular plants

are much less reliant on free water than seedless vascular plants.

Much like amphibians, seedless vascular plants relied on wet

and moist conditions for the success of their reproductive cycles (Rost 1998).

The evolution of the ovule, the seed, and pollination, allowed for the

successful radiation of gymnosperms throughout the Mesozoic era and into our

current period (Evert & Eichhorn 2013).

All seeded plants are heterosporous, producing megaspores

which give rise to megagametophytes, and microspores which develop into microgametophytes

(Evert & Eichhorn 2013).

|

| Life cycle of gymnosperm seed |

The ovule

consists of a nucellus, enveloped by a single integument, a protective layer,

and has an opening at its apical end called a micropyle. Within the nucellus, a

single megaspore is retained, which in turn evolves into a megagametophyte

(Evert & Eichhorn 2013). Following fertilization, the ovule matures into a

seed. The seed consists of a mature embryo which is self-nurturing and is

surrounded by a protective coat and able to be transported away via various

mechanisms, allowing for greater survivability and radiation (Reece &

Campbell 2012). The term gymnosperm means naked seed, as the seeds are uniquely

formed naked on the surface of modified leaves called scales.

In my next post I will look at the various phyla within the

gymnosperms.

References

Evert, R.F., Raven, P.H. & Eichhorn, S.E. 2013, Biology of plants, Eighth edn, W.H.

Freeman and Company Publishers, New York.

Reece, J.B. & Campbell, N.A. 2012, Campbell biology, 9th (Australian version) edn, Pearson Australia,

Frenchs Forest, N.S.W.

Rost, T.L. 1998, Plant

biology, Wadsworth, Belmont, Calif.

Willis, K.J. & McElwain, J.C. 2014, The evolution of plants, Second edn, Oxford University Press,

Oxford.

slide player.com Date Unknown, Gymnosperm

ovule to seed, image, viewed April 2018, < http://slideplayer.com/slide/6669888/>.

oshonews 2016, Permian period with gymnosperms, image, viewed April 2018, <

https://www.oshonews.com/2016/05/06/the-permian-period-supercontinent-pangea-and-earths-largest-mass-extinction/>

What was it about this time that allowed some of the largest plants and largest animals to flourish? Was there a relationship between the two?

ReplyDelete